There’s a reason why the Discovery Channel has a show dedicated to Alaskan fishermen. “The Deadliest Catch” portrays this field as an extremely harsh and dangerous work environment for the fishermen, but this also holds true for those of us who choose to practice medicine in it.

The author of this is Ken Young. Ken was a friend, coworker, and colleague who killed himself in November of 2017.

July 10, 1974 – November 19, 2017

I met Ken when he volunteered as a patient for a course I was instructing. Ken had been through the course previously and loved it so much he wanted to come back to support it as a patient. His enthusiasm for remote medicine was seemingly endless. He and I stayed in contact after the course and when he was leaving his position as a Vessel Medical Officer on the Kodiak Enterprise he recommended that I take his place. He and I chatted at length before I took the position and continued to chat while I was on the vessel. We had planned to work together in the future.

I have no idea what was going through his mind in the final moments he was alive, but I don’t believe those thoughts reflect who he truly was. Ken had a lengthy military career that brought him an immense amount of pride and went on to work as a remote medical provider in a variety of capacities. In the weeks before he died he deployed to Puerto Rico to provide aid. As with most suicides his death came as a shock to those around him.

My intention in reposting his writing is to help remember the Ken that I knew. The guy who was deeply passionate about many things including remote medicine.

If you are in crisis call the suicide prevention hotline at 1-800-273-8255. Alternatively, call a friend or call me at 315-484-8087.

If his estate now holds the copyright on these writings and wishes them to be removed I will do so.

Originally published on LinkedIn

Care on the Bering Sea

There’s a reason why the Discovery Channel has a show dedicated to Alaskan fishermen. “The Deadliest Catch” portrays this field as an extremely harsh and dangerous work environment for the fishermen, but this also holds true for those of us who choose to practice medicine in it. According to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics (possibly until the recent targeting and assassination of Police Officers), fishing in the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska was the most dangerous job in America. The hunt for Alaska Pollock is nonstop, as is the risk for injury.

This writing is a glimpse into this field to provide an understanding as to why this is. After just three weeks on the fishing vessel we had a small engine room fire that partially crippled us. Thankfully, we safely made port in Alaska’s Aleutian island of Akutan for repairs, but I treated two of our crew-members for minor carbon monoxide poisoning from the post fire cleanup. Comparatively the fishing vessel Alaskan Juris sank this same day forcing 46 crew-members to abandon ship. I guess we made out pretty well, unlike that vessel from another company. This is not what most people would call a typical voyage at sea.

A week and a half prior to the engine fire, I treated an anterior septal STEMI. This is the type of heart attack commonly referred to as the “Widow Maker” by medical providers due to its’ severity and morbidity. When I think of it in retrospect, it was an intimidating situation, especially as I now ponder how I would’ve handled it if it had turned into a full cardiac arrest while we were further from land. I’m glad I was able to care for, and transport, this patient without out too much difficulty, since we were moderately close to the Dutch Harbor clinic. The “M.O.N.A.” protocol (Morphine, Oxygen, Nitrates, Aspirin) went a long way by reducing cardiac preload until we got the patient to the Dutch Harbor clinic. Luckily there happened to be a critical care medical flight ready at the local airport and was able to fly my patient to Anchorage, three hours away, when usually it’s a 6 hour delay due to the fixed wing aircraft’s two-way flight from Anchorage and back. The patient survived to be treated in the Anchorage cardiac catheter lab and is now home recovering.

The challenges in this environment build up quickly. While I’m creating a homemade olfactory test from coffee grounds and spices from the galley for a neurologic exam, I’m also researching how to fill empty oxygen bottles on a small island with limited resources. Remote or Wilderness Medicine is practiced in this environment, well known for its unique challenges, including: Isolation from definitive care; Limitations in logistical support with limited inventory and difficulty in resupply; Extreme weather conditions, such as high winds, wave impact, motion, salt water, freezing temperatures, and risk of immersion; Trauma; Illness; Seasickness; Cramped living conditions that are difficult to keep clean and lead to the risk of mass infection; and more. To practice successfully in this environment one has to be a bit of a (Very Junior) Primary Care Provider, Nurse, First Responder, Lab Technician, Dentist, Safety Executive, and Counselor all rolled into one.

Dutch Harbor on the island of Unalaska is home to the Iliuliuk Family Health Clinic. It has 3-5 providers, ultrasound, x-ray, lab, and a dispensary (not a full pharmacy). Although this is a “Family Practice / Urgent Care” clinic it is considered remote care because of the less reliable access of resupply and MEDEVAC resources. Limiting their care, there are no CT or MRI machines, and any patient with a condition that’s really troublesome must be flown to Anchorage via MEDEVAC. Unalaska is a beautiful yet often dreary spot. Summer boasts lush green, mossy, and often snow topped mountains surrounding the various coves where vessels make port. Winter the island resembles a frozen wasteland with treacherous and icy gravel roads where one slip and a vehicle can easy find itself in the sea. Still despite it often being fogged-in, its beauty can be hidden. The fishermen here have a saying, “There’s a beautiful woman hiding behind every tree on the island.” So as you can guess with no trees the women can be scarce. Yet, the beauty of the island and the sea that surrounds it defy verbal attempts at description.

Other than the heart attack and a case of kidney stones, it’s been the usual myriad of maladies on the vessel; pharyngitis, coughs, urinary tract infections, muscle strains from lifting, and the occasional hand wound needing repair, to name a few (note: giving sutures while rocking back and forth on rough seas is not an easy task). Once, a heavy fillet pan fell on the head of a crew member, causing a mild traumatic brain injury with noticeable deficit of the 4th cranial nerve. Another time I provided nutrition counseling for a patient who suffered from what I suspected to be diverticulitis. The majority of my day is often spent doing safety surveys, treating sea sickness or doling out over the counter medications, including Dayquil™, IcyHot®, ibuprofen, bottles of cough syrup, wrist braces. The paperwork each day never ends; medical releases, claim forms, Coast Guard forms, drug tests, inventories, meeting notes, etc. As a Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Medic I’m also head of the vessel safety committee. I assist in conducting safety inspections, oversee the monthly fire, man-overboard, and other emergency drills, and hold safety meetings that track the issues brought forward by the crew.

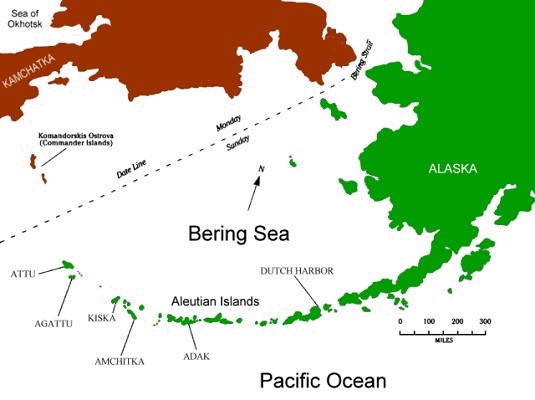

The life of a Vessel Medical Officer on an Alaskan waters fishing vessel is interesting. My ship is about 300ft long and has its own processing factory below deck. We operate in the Bering Sea, often closer to Russia than the US, in a region infamous for its treacherous waters. The 130-man crew is a multinational collage of Vietnamese, Filipino, Latino, and African Tribesmen, to name a few. The deck and engine room crew are tough, not wanting to seem weak and see “Doc” for any issues other than the frequently needed placement of stitches. The factory crew works 16 hour shifts with a mere 8 hours off, for 7 days a week for months on end, and they need regular attention. There is even one crew member that comes just to talk through his relationship issues causing him anxiety. It’s a good crew, with a family feel of the individuals. Their backgrounds are mixed, and many seem to be escaping something to work on the Bering; financial hardship, legal issues, nationality concerns, or relationships gone bad top the list of reasons. Others are career fishermen who live for the hunt.

As a Vessel Medical Officer I practice care under the International Maritime Labour Convention 2006 (MLC, 2006) Regulation/Standard A4.1.4.a. This standard directs the appointment of a seafarer who is in charge of medical care and administering medicine. Since we operate sometimes more than 10 hours beyond definitive care, regulation requires that the provider’s training meet the requirements of the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers of 1978 (“STCW”). Utilizing my certification as a Medical Care Provider in Charge, which is a US Coast Guard endorsed STCW certification, I practice Advanced Life Support and Primary Care Provider/Nursing skills offshore. I have the support of Telemedicine via email or satellite phone. I provide a full spectrum of pharmacotherapuetics and medical procedures with the assistance of telemedicine using specific protocols. Many interventions, antibiotics, and other medications I can provide instantly based on my clinical judgement of a patient, and merely document the patient contact, assessment, and treatment plan back to the telemedicine team. If they notice something I missed, they educate me, correct my course of action, and I follow up. For more invasive procedures and medications, like the administration of heavy duty narcotics or minor surgical procedures, I must confer with telemedicine before treatment. In addition to following Maritime regulation, I also follow OSHA rules for reporting.

Comparatively to crews from other vessels and the companies they represent I feel lucky. I was contacted by a member of our crew who went to another vessel, with another company. They needed to get unofficial medical advice. For example what to do for a poor guy who is passing a kidney stone, especially when they don’t have telemedicine support and someone decided to steal all the narcotics on board. I “reminded” the Captain what he learned in his maritime first aid class he attended 4 years prior. Suggesting options considering the medications and supplies they had on hand. I asked our former crewman what life was like on that smaller vessel and the response was, “It’s certainly a wild crew. The last captain got fired not because he smoked meth with the crew but because he had diabetes complications and refused to steam to the clinic for 2 weeks after the doc told him to. Then he ate all the painkillers for funsies before he left… And still tried to sue the company. Another guy got fired for trying to have sexual intercourse with a skate [Stingray]. Multiple people recorded him for some reason. And lastly, a guy had to be med evac’d for a methadone od (seizure). He wasn’t fired for some reason and is still on board.”

The company holding my contract is one of the largest seafood producers in the world. They are constantly making improvements for the safety and well-being of the crew, and as such they are one of the first companies to have a dedicated medic assigned to their vessels. As dictated by the Maritime Labour Convention & OSHA, smaller companies simply have the Captain, Mate, or another seafarer provide the first aid, but this individual is primarily concerned with their own duties and can sometimes view providing medical care as a hindrance. The industry standard is a 5 year requirement for re-certification of maritime first aid/medical training, posing issues because healthcare guidelines can change a lot in 5 years. Additionally, skills learned and practiced once are often forgotten by these seafarers turned part-time medical providers. Fortunately the company I work for is large enough to see the financial and legal benefit of having an OSHA experienced medic on board their largest vessels.

I manage the “Sick Bay,” which is also my personal stateroom. There’s one bed, laptop, refrigerator, sink, many cabinets, and a bathroom & shower I share with the Mate. I also have access to an autoclave for sterilizing surgical equipment. I basically have a fully stocked “Medical Chest” or dispensary onboard, (including some of the strongest controlled narcotic medications) for which I manage the inventory. I have almost everything I could need to care for a patient. I’ve been working with the company to replace my standard AED with a Lifepak® and purchase an iStat®, a portable complete blood laboratory.

The Galley/Mess (kitchen/dining room) has a large medical locker. The numerous tables provide a mass casualty treatment area in the event of emergencies. We have a Stokes litter stored under the wheelhouse (where the Captain controls the vessel), and an emergency work skiff (small boat) strapped on the bow that’s lifted off by a crane four decks below to the sea. We use it for our “man-overboard” drills that are conducted once a month. During these drills I randomly grab a life preserver and toss it overboard, wait a few moments and hit the alarm. I run on deck and point in the general direction of where I saw it last. The Captain conducts a special “Williamson Turn” and returns to the spot where the alarm is set off, the skiff is lowered to the ocean below via crane and launched to recover the “patient” to me.

Prior to my arrival we had no true medical record system, just various spreadsheets and text files. I have a limited amount of patient history on a crew of workers that can barely speak English. To correct this, in my spare time I have downloaded and modified the software code of an open source computer medical record system called “OpenEMR” to give us a way to track patients and keep my workups/charts organized while remaining HIPAA compliant. Its installation wasn’t easy; the internet has been 10 times slower than dial up, when it works at all. When not taking care of a patient or doing safety-related work, my nose is buried in medical books. I’m always trying to learn more, as well as research the conditions I’ve seen so far to critique my work. I always strive to be a better, more educated, and competent provider for my patients.

Despite my studies at different schools and programs, there are definitely topics that I needed to focus on in preparation for this. Every role and every company is different. Key areas of this specific assignment are: OSHA standards of reporting, antimicrobial therapy, general nursing, setup & use of a sterile field or aseptic technique, safety assessments & risk mitigation, clinical assessments, general counseling for stress management, nutritional coaching, medical supply inventory control, and more. Luckily I was trained in procedures that many paramedic programs don’t cover. One has to be a clinician and not a mere technician, having a solid grasp of the diagnostic process and therapeutic thresholds. In a mere 5 months on my first contract some of the specialized exams and procedures I’ve conducted include nail trephination of a digit that was crushed, ganglion cyst reduction, olecranon bursitis reduction, advanced neurologic exams, exams using a ophthalmoscope, temporary dental fillings, extremely detailed focused assessments, and much more. I will say that the Remote focused EMT course I attended through Remote Medical International was outstanding; it aided me in certifying not only as a Remote EMT, but as an MCPIC, which is the standard for this position. The basics taught in remote/austere medicine are invaluable, but they are still just the basics. To be a good provider in this environment there’s so much more to learn. I’m very glad I pursued advanced training beyond my R-EMT, including remote critical & primary care para-medicine. This job requires you to be a Swiss Army knife of a medical practitioner. It’s quiet and boring one moment, and stressful the next.

Take the night prior to this writing as an example. I sat awake all night as I monitored a patient’s vital signs, while he rested in the bunk that also serves as my nightly bed. Hypotensive with tachypnea, and suffering from what I suspected as Hyperglycemia Hyperosmolar State with a differential of Diabetic Ketoacidosis; I checked his blood glucose every 30 minutes. He had no prior history of Diabetes. Above him a bag of IV solution hung, next to him the 12 lead EKG continuously monitored his heart. As directed by telemedicine, I give him .25ml of Humulin insulin via IV, and watched as his initial blood glucose level went from 264 to 21. Personally I thought we should go with fluids or at most .15ml Humulin, since he’s insulin naïve, but the doctor was more aggressive and knows much more than I. It was a long night of playing “balance the glucose,” with a patient who fluctuated in and out of responsiveness, back and forth between hypo & hyper glycaemia. It was intervention after intervention, test after test; IV line, cardiac monitoring, urinary catheter, urine tests, insulin, glucose to balance the insulin, and more. I wish I had an iStat® to check his potassium & sodium levels. He was seen at clinic a week and half prior for a seriously infected wisdom tooth abscess, yet he’s been on antibiotics and asymptomatic of any other conditions since. My mind raced through differential diagnoses.

While the patient was alert and oriented, I consoled him about his condition. He was in tears fearing he would have “The Sugar” the rest of his life. I empathize with him, yet preferred him emotionally distraught and talking to me compared to the alternative I witnessed so many other times that night. Times in which he became diaphoretic, drenching the bed in sweat, and unresponsive to verbal stimulus, thus calling into question his survivability. It was nerve-racking watching his condition act like a yo-yo right in front of my eyes for hours, knowing I’m the only medical provider, and that the responsibility for him was mine with definitive care 14 hours away if we diverted immediately. That’s not even completely definitive, but the clinics at Dutch Harbor or it’s even smaller sister in Saint Paul with their extremely limited resources.

As the primary advocate for my patient, the Captain and myself heatedly debate over whether or not to divert the boat to Saint Paul, yet another location in the Alaskan Island chain. It was a hard position being in, trying to balance the needs of my patient (which obviously come first), and the demand of the business at hand. The company medical representatives on the phone agreed with me, always supporting taking care of the crew. The Captain for this voyage didn’t completely realize the position I was in, that it was my job to take care of the patient, as well as protect him and the company from being drawn into a legal deposition regarding a worker’s compensation claim, or worse. The Captain was heated we had to stop fishing, especially after the time already lost due the fire, but in the end we diverted to the clinic on Saint Paul. In sickbay before we departed, I had my patient somewhat stabilized through the night. That was until our movement to the skiff caused him to become dizzy and vomit. Just prior to the skiff ride his blood pressure was tanking at 66/40mmHg and he was becoming diaphoretic.

Saint Paul doesn’t have a large dock, so we couldn’t get the vessel in to tie-up; we were forced to take a smaller craft and skiff the patient from the fishing boat to land. A couple of deckhands and I donned our life vest type “floatcoats” and hardhats, and boarded the small skiff on the deck of the much larger fishing vessel. Along with my patient, we were lowered into the pitch dark of early morning with only the main vessel’s lights illuminating the deck for us, until we dropped. We hit the turbulent water below and raced to the shore where an ambulance was supposedly waiting. The bright lights of our fishing vessel became smaller and smaller as the black of night closed in around us. The few lights of a small fishing village became closer on the horizon as the skiff felt like it was trying to take flight on the jagged waves. We went through what I thought was a cove, and finally found the ambulance next to the small dock where we tied up. I turned my patient over to the Saint Paul clinic PA, via the awaiting ambulance, along with a verbal report and my 3-page patient chart describing everything that happened. Once finished, we raced back to the vessel, water spraying everywhere on the ride. I hadn’t noticed the spray on the way to land because I was too busy keeping my patient, his IV bag, and my medical kit from being tossed into the frigid water. I returned back to my room to disinfect, and was about to lie down and finally rest, when there is a knock at the door…“Hey, uh Dok-tor. . . “

This is remote medicine, this is my passion.

About the author:

Kenneth Young is a Remote-EMT, Diver Medic, Nurse Tech, and candidate for Fellowship of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine. (Posthumously awarded FAWM – DT)