At times the medicine we practice in a remote location may not be too different than what would be done in a well resourced setting however the environment necessitates that providers be able to perform other skills not directly related to the care being rendered.

It may be necessary to improvise a litter, use a non-standard patient transport vehicle, build a shelter, navigate with a map and compass, or signal your position to others on the ground or in the air. The last of those items is being addressed in this post.

Seeking out basic wilderness survival training is really useful even if you will only be traveling through the wildness but not intending to work in that environment. Donner Party anyone? Unexpected weather or a vehicle issue could suddenly turn a long drive in to a much more dangerous situation.

I was fortunate to receive some basic wilderness survival training through the Civil Air Patrol when I was in high school, refreshed and expanded my knowledge as an instructor on land navigation courses through New York State Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Services, and picked up some tips and tricks from experts and colleagues along the way.

Reading about skills will never replace using them, especially using them in field conditions, but a good place to start reading is the freely available US Army Field Manual Survival FM 3-05.70 formerly known as FM 21-76.

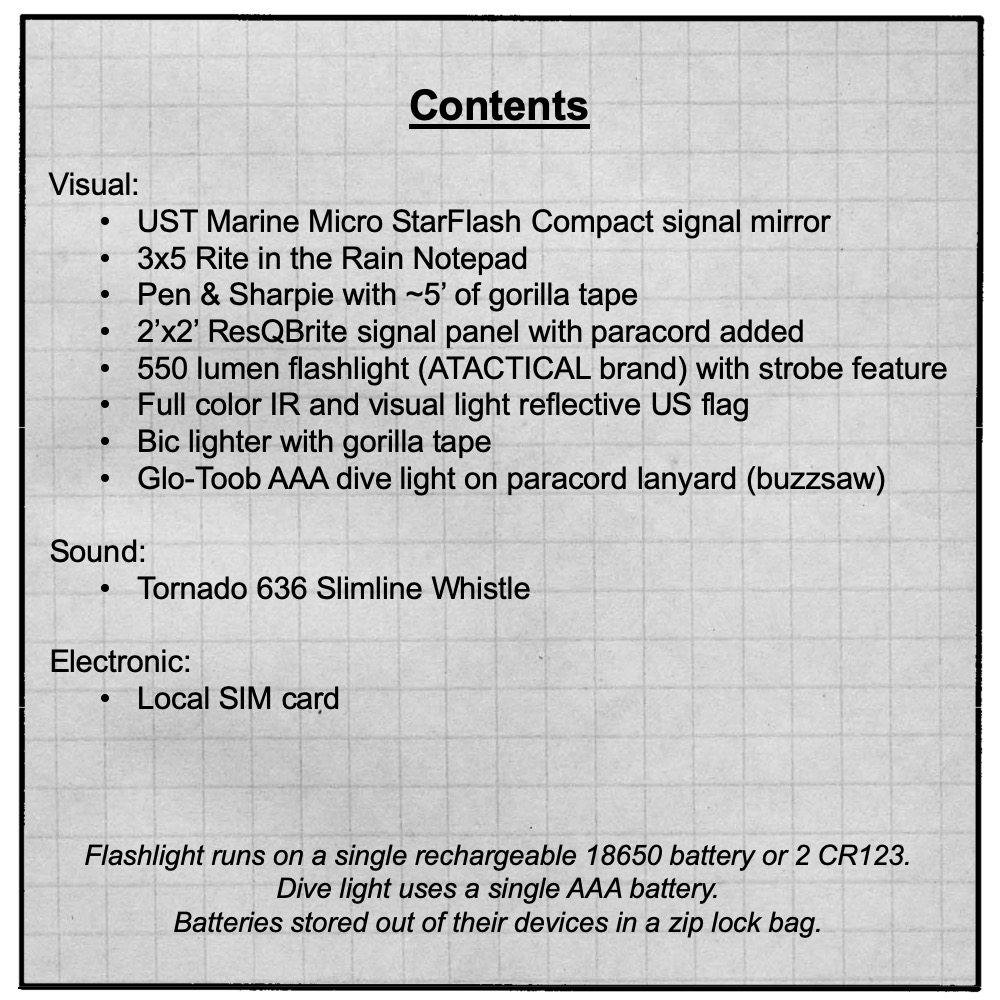

Chapter 19 of the Survival field manual addresses signaling and breaks the methods down in to visual and audio plus adds some standardized codes/signals that may be used. The manual lists a number of different devices with their pros and cons.

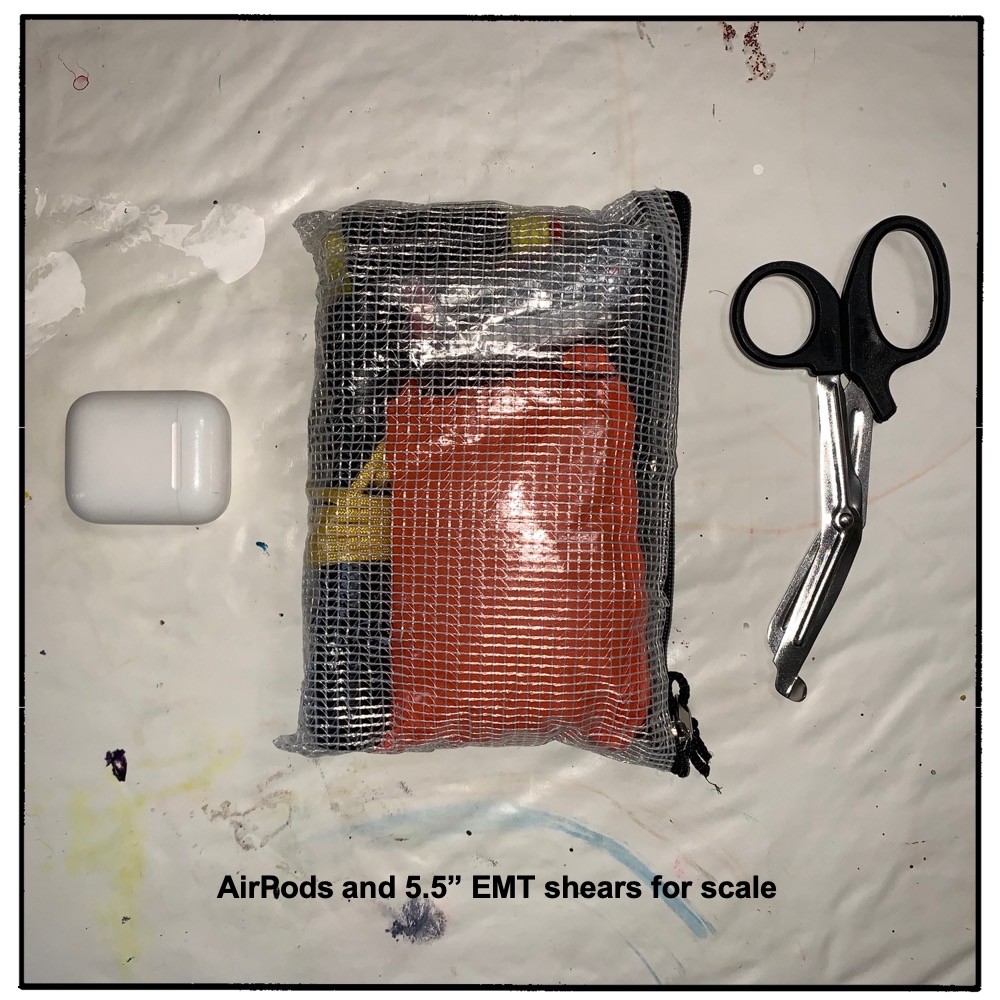

My kit uses some of those methods, but also utilizes largely civilian items that one might procure in an outdoor supply store. I try not to travel with much military gear as it can attract unwanted attention and raise questions about what I’m doing (even when I’m being completely honest).

The present kit is designed to be used in a very rural conflict area where I am not considered a combatant. The most likely scenarios in which I would need to signal someone are:

-

-

- Disabled vehicle and signaling others on the ground to avoid the vehicle

- Patient evacuation with a ground or air retrieval platform

- Signaling an UAV to coordinate evacuation

-

I carry this kit in a 30L daypack that has some other survival related items including additional communications tools, map and compass, some medical stuff, and warm, dry clothing. On my person I always have an iPhone, issued android phone, folding knife or multitool, flashlight, and local currency.

Contents

Visual:

Sound:

Electronic:

•Local SIM card