I remember trying to sort out if I couldn’t stop the attack, if I was paralyzed by fear, or I was unwilling to stop it. I recall having their blood on me.

Glossary:

ISOF: Iraqi Special Operations Forces

TSP: Trauma Stabilization Point

MSF: Doctors without Borders

VBIED: Vehicle Borne IED

Daesh: Arabic name for IS/ISIS/ISIL, possibly derogatory, largely interchangeable with IS/ISIS/ISIL. There’s more to it than that, but can we just generally agree, fuck those guys?

Preface:

This comes from a journal I kept during my time in Kurdistan and Iraq. As much as I could I did a brain dump at the end of each day. Most days I was exhausted from the jet lag, the work, the heat, and on some days from the emotional toll.

Some editing has been done for clarity, but I am intentionally keeping this a bit raw and in many cases using the words I wrote in country which are denoted by the italicized text.

I have redacted some details. War is hell. Other accounts of those details may come to light in time, but I have no intention of publishing them.

This is a far from complete account of my experience. I mention just a fraction of the patients we saw each day. On some days I treated a dozen massive traumas plus dozens more of severely ill civilians. For whatever reason certain patients stood out in my mind at the end of the day and those made it in to my journal. They weren’t always the most severe, just what I remembered.

On June 21st 2017 I sat in the home of a dear friend, Sagvan, as the news broke that Daesh had destroyed the Great Mosque of al-Nuri. Sagvan is proudly Yezidi and Kurdish. The al-Nuri Mosque was a Muslim historical site possibly dating as far back as the 12th century.

Despite this site not being part of his faith Sagvan and the other Yezidi present for dinner that night all felt it as a loss. I was vaguely aware of the distant history of the mosque and of its more recent infamy as the site for many of Daesh’s leader’s speeches. It was in that building that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared the caliphate and on top of that building that flew the black flag since June of 2014.

I saw the site as a loss for the world as it represented history, architecture, and craftsmanship as well as a place of worship. I also saw the destruction of the mosque as a potential indicator of the mindset Daesh was now operating under. My inference was that the willingness of Daesh to destroy a structure that held significant symbolic value to them without a clear tactical purpose (eg killing soldiers inside the mosque, delaying access to retreat routes) meant that they were becoming more desperate.

I suspected that more suicide bombers would be used or perhaps other suicidal tactics with worse outcomes ( eg deploying of nerve agents). This belief would prove to be partially true in the following days as the number of female suicide bombers deployed dramatically increased. I am trying to find a citation that supports or disputes that assertion. This increase was reported to me by the westerners and Iraqi soldiers I would go on to work with.

In her paper, Female Terrorists in ISIS, Al Qaeda and 21rst Century Terrorism, Dr. Anne Speckhard states “There is evidence now that as ISIS gets more hemmed in and needs to replace the male cadres who have already carried out suicide missions, women may also be sent as suicide bombers.”

I knew that by the time I arrived in Mosul there would be fierce house to house fighting and I believed that the enemy was more desperate than ever to kill as many as possible before being killed themselves.

My team in Kurdistan had already been told that many Daesh fighters, especially local ones, had melted back in to the communities they came from. It wasn’t know if they were simply trying to hide and resume their pre-Daesh lives or if they were forming sleeper cells to carry on the mission in a guerrilla war.

Finally, it was known that Daesh had quite a bit of heavy machinery and plenty of time to fortify or mine the city. I realized that it very well may not be known until something goes wrong just how well prepared Daesh was for the fight in Old City Mosul.

One fleeting thought I had was that perhaps the capture of one or more western aid workers could be used by a partially defeated Daesh to secure their escape from the city.

Evening prior to departure for Mosul:

Sleeping at the house Global Response Management rents. I’m sharing a room with one of the team leaders from GRM, Chris, who will be going to Mosul tomorrow. First night I’m not sleeping next to Stolley and John. We’ve spent nearly a month together, often sleeping a few feet apart.

That night I had the first and only nightmares during the trip.

Two of my teammates were murdered by a drunk boyfriend. I didn’t stop it.

I remember trying to sort out if I couldn’t stop the attack, if I was paralyzed by fear, or I was unwilling to stop it. I recall having their blood on me. Needless to say, I didn’t sleep terribly well that night.

Day 1 – 6/30/17

I awake shortly after dawn in Erbil at the GRM house and was happy to see everyone else was still sleeping. I went downstairs to a spacious living room with floor to ceiling windows to read a bit. Reading was challenging as I was excited to be going to Mosul and a little sad to be sending off the two guys I had spent a wild month with.

John and Stolley stayed in the same house and would be flying out the next day. Eventually the house came to life. Members of GRM plus my team emerged, greetings were exchanged, travel plans for the day discussed, and good byes were said. I think Stolley said something to the effect of “Don’t get beheaded. It wouldn’t be a good look for you.”

I loaded my gear in to one of GRM’s Hiluxs and Chris and I left to pick up Hasan, an ISOF soldier who worked with us as our translator, fixer, and friend. With Hasan retrieved we stopped by a grocery store on the way out of town for water, drinks, dried food, and snacks. I secured a few Wild Tigers, canned tuna, and cups of noodles.

A few shots from the drive in to Mosul

It is remarkable how quickly life returned to some semblance of normal. Neighborhoods liberated weeks ago already had businesses open and people going about their day-to-day activities. We drove past shawarma shops, pool halls, shisha bars, grocery stores, folks selling produce out of trucks, welding shops, clothing vendors, and automobile repair shops. I didn’t expect to see all of this, but it makes sense. People are moving back, people need money, people need services. Daesh was known for many things including their love of posters, painted signs, flags, and other visual signs of control. I saw none of those on the drive through these reclaimed neighborhoods. There were walls with blocks of black paint which I suspect cover some of those things.

Although military vehicles frequently traveled these streets there wasn’t a constant military presence. If you only looked at an undamaged building, of which there were a few, or watched kids playing you might not know that this city was still considered a war zone.

The shot below wasn’t taken on the drive in, but I saw this multiple times on that drive. This is a family with what is likely all they own moving back in to the city even as smoke rises in the distance showing the most recent VBIED or airstrike. I saw hundreds of people carrying bags and suitcases walking back to the city as well. In many cases these families were moving back to homes vacated days or weeks prior by Daesh. Some of these people would undoubtedly be killed when they found some of the IEDs left behind by Daesh. As they retreated Daesh left IEDs in ovens, kids toys, vehicles, and anywhere else they might be encountered by civilians. No strategic purpose, simply to maim and kill civilians so that the legacy of Daesh would persist even as there bodies rotted in mass graves or floated down the Tigris.

When we were a few kilometers from the TSP Chris got a call saying that they had been notified that there would be a dozen or more chemical casualties coming in, possibly chlorine but details were scarce. We drove directly to the TSP and I found a calm group of comprised of Americans, Iraqis, an Australian, and a Brit prepping to receive the casualties. They were setting up a decon area, getting IV bags spiked, and resetting from the previous casualties who had likely left just minutes before. One guy, the Brit, had a Tyvek suit on pulled up to his waist with the arms tied across his stomach. He was wearing rubber boots and I noticed a plate carrier near by with a gas mask clipped to it. Everyone else was wearing typical field clothing which was a mix of military pants, t-shirts, sometimes a matching military top, some had armor or a chest rig on. This was far from the resource rich hazmat training I had been part of before. If you had brought a gas mask or hazmat suit you were welcome to wear it but it wasn’t something we were pulling out of a large Conex box out back or off the hazmat truck when it arrived. There was no Conex box, no hazmat team, hell we had a limited amount of water with which to decon our patients. There was a large metal container in front of the TSP which held 200 or so gallons and got refilled once a day.

Through some good pre-trip research and networking I have developed very realistic expectations of my working environment. This was effectively guerrilla medicine. Supplies were transported in cardboard boxes and duffle bags, shelves and tables were made using whatever materials we found in the building we happened to inhabit that day or that week, and the fundamental expectation was that whatever was built would be irrelevant in a few days when we moved as the fighting moved.

My weeks in Kurdistan prior prepared me well for this. On that mission we accomplished a few things, which will likely be covered in another writing including delivering supplies to a hospital about 30 miles from the Syrian border. Those supplies were transported through friendly and unfriendly check points and had some value on the black market.

From my journal that night:

Great day in Mosul. Multiple traumas, illnesses, crush injuries.

Credible threat of 7 suicide bombers targeting us. 5 min bail out time.

We are on the main strip to the front – battle dozers – land of mad max vehicles.

Children with dehydration, elderly woman with suspected sepsis, mother who was shot in the abdomen 5 days ago presenting to us with a serious infection.

On the roof [of the ISOF house], listening to explosions 2.5 km out. Beyond sniper range. Still could be in mortar range.

Insight about the type of people who stay in war zones from Anthony… 70% have father issues, 30% are sociopaths. He has father issues. Hopefully, I’m in the same category.

Note:

When I talk about a “great day” I am not taking any joy in the suffering I saw. I love the Iraqis and the Kurds. These are incredibly warm, hospitable people who treated me with more kindness than many American’s I have known. If I was stranded somewhere with no money and needed a place to stay as well as a meal I would rather be stranded in Mosul than Manhattan. When I say “great day” I mean that I made a difference, I had a clear sense of purpose, I was able to slightly improve an individual’s condition, and that I felt as if I was part of a team, a tribe. If you take offense at my words so be it, you are not the intended audience. If you smile or laugh based on my words then you get it.

One of the many battle dozers that passed by our TSP. These vehicles and folks driving them were essential to the military operation in Mosul. Seeing one with intact bullet resistant glass was uncommon. They usually got replaced before complete destruction, but they almost always carried evidence of leading the charge.

Looking out from the TSP. Taken shortly before we evacuated that night. Facing towards the areas of heaviest fighting. The majority of our casualties arrived from the road obscured by the headlights. The black smoke was likely from an airstrike.

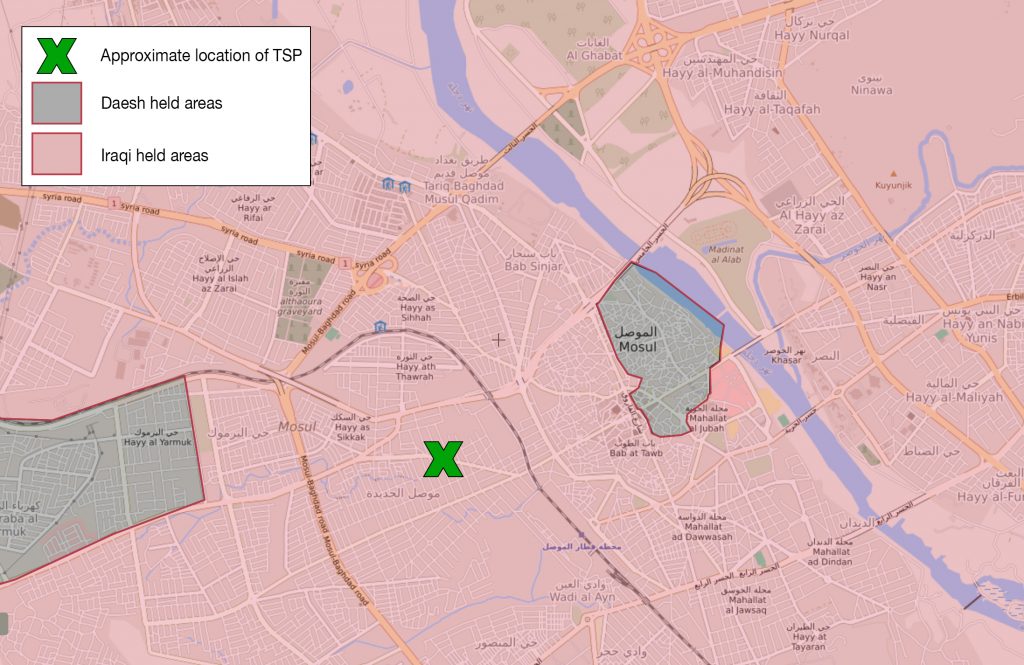

A map for reference. Grey was Daesh controlled, red was Iraqi. The bulk of the fighting was focused on the area still controlled by Daesh along the Tigris.