‘Tis the season for that sore throat. Whether it’s overly belting out those holiday carols, or just that nasty bug that won’t give up; sore throats are a problem this time of year. Sore throats can be difficult to assess and treat in a remote environment.

The author of this is Ken Young. Ken was a friend, coworker, and colleague who killed himself in November of 2017. He was posthumously awarded the Fellowship of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine.

July 10, 1974 – November 19, 2017

I met Ken when he volunteered as a patient for a course I was instructing. Ken had been through the course previously and loved it so much he wanted to come back to support it as a patient. His enthusiasm for remote medicine was seemingly endless. He and I stayed in contact after the course and when he was leaving his position as a Vessel Medical Officer on the Kodiak Enterprise he recommended that I take his place. He and I chatted at length before I took the position and continued to chat while I was on the vessel. We had planned to work together in the future.

I have no idea what was going through his mind in the final moments he was alive, but I don’t believe those thoughts reflect who he truly was. Ken had a lengthy military career that brought him an immense amount of pride and went on to work as a remote medical provider in a variety of capacities. In the weeks before he died he deployed to Puerto Rico to provide aid. As with most suicides his death came as a shock to those around him.

My intention in reposting his writing is to help remember the Ken that I knew. The guy who was deeply passionate about many things including remote medicine.

If you are in crisis call the suicide prevention hotline at 1-800-273-8255. Alternatively, call a friend or call me at 315-484-8087.

If his estate now holds the copyright on these writings and wishes them to be removed I will do so.

Originally published on LinkedIn

Is it Strep Throat or a Virus? How to Tell & Treat in the Remote Environment

‘Tis the season for that sore throat. Whether it’s overly belting out those holiday carols, or just that nasty bug that won’t give up; sore throats are a problem this time of year. Sore throats can be difficult to assess and treat in a remote environment. So, if a crew member on your vessel, or an expedition member up in the mountains is suffering with this condition and it’s your duty is to care for that individual, then there are things you should be aware of.

There are two common causes that result in a sore throat or “pharyngitis”, one is a bacterial infection and the other is a viral infection. A medical provider must first know the difference between these two to properly assess and treat a patient. If you’re not in the role of a standard medical provider, having merely been introduced to your medical role via a maritime medical class or something similar, then the medical science behind this difference may not be apparent to you. Specific science aside, the biggest thing to know is bacterial infections are treatable by antibiotics, whereas viruses are not. You may ask, “why not treat with antibiotics just in case?”. While antibiotics are often key to treatment, there is a problem with antibiotic medications. Some of these drugs that used to be standard treatments for bacterial infections are now less effective or don’t work at all. When an antibiotic drug no longer has an effect on a certain strain of bacteria, those bacteria are said to be antibiotic resistant. So treating a virus with antibiotics is not a good thing because it build this resistance, possibly making it more difficult to treat conditions in the future.

Common bacterial infections of the throat arise from the exposure to Group A Streptococcal bacteria, also known as GABHS. This is what’s referred to as a “Strep Throat”. GABHS is the most common bacterial cause of tonsillopharyngitis, but this organism also produces acute otitis media; pneumonia; skin and soft-tissue infections; cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and lymphatic infections; bacteremia; and meningitis. Also keep in mind for those crew members who interact with a GABHS patient, that it is transmitted via respiratory secretions, and the incubation period is 24 to 72 hours. So try to keep the rest of your crew from contracting it as well, and put a medical mask on that patient.

Viral infections are not typically treatable by antibiotics. Viruses are usually allowed to run their course and pass in time with only relief of the various symptoms that accompany the virus, like cough, sore throat, fever, sniffles, or such possible. Most important is to ensure the patient with a virus is well hydrated in order for that virus to pass.

If you’re a provider with access to antibiotic mediciations such as many vessels at sea, then you need to know which ones to use to treat these conditions. Yet there in lies the delemna, when and if to use them, because these infections are treated differently. A throat culture and a dedicated laboratory is the diagnostic standard in differentiating between the two conditions, but unless you’re co-located with your own hospital or have an enhanced medical bay onboard then your options for definitive testing are limited. There are rapid antigen detection tests [RADT] for GABHS that you may have access to in the remote enviroment, while these tests are specific, they are not always accurate. Still, you need to treat this condition properly.

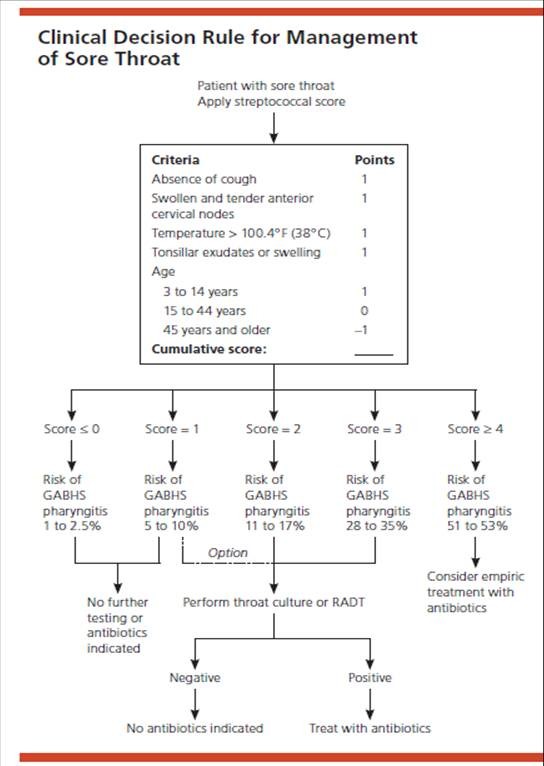

This is where “Centor” Criteria comes in. Centor criteria is a clinical decision rule that may identify the possibility for a bacterial infection that can be treated via antibiotics in comparison to a viral condition that should not receive these medications.

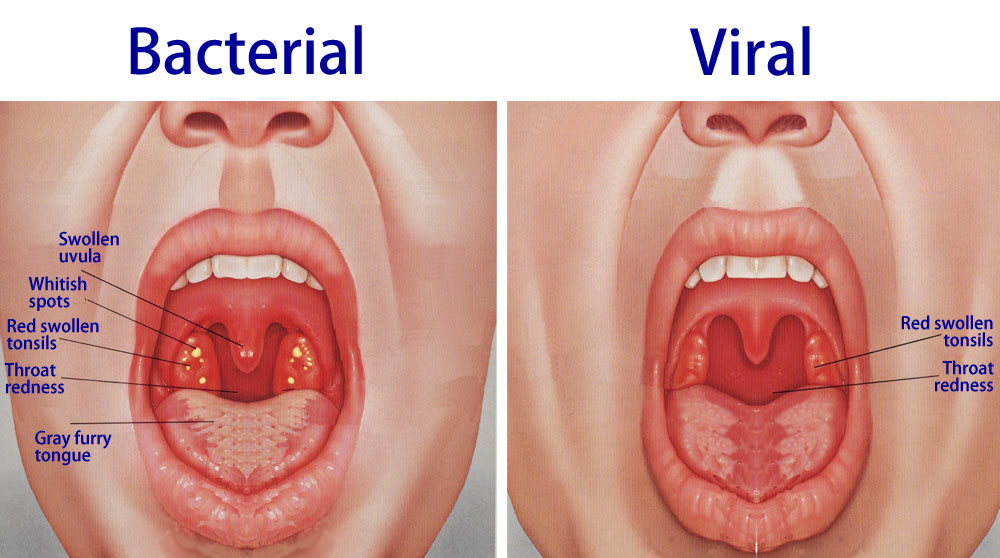

Patients are evaluated on four or five criteria, with one point added for each positive aspect of the assessment. Signs and symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis include temperature greater than 100.4F (38°C), tonsillar exudates (white spots), tender anterior cervical adenopathy, and absence of cough. Each of these symptoms are awarded a point in the Centor criteria scale, with a fifth point being used in a modified scale to include age of the patient. Cough, diarrhea, coryza are more common with viral causes. Differences in these symptoms build the values for the score, and denote if further testing is necessary or if antibiotic treatment is advised. See chart above for details.

In cases of bacterial phlarangeal infections the use of Penicillin (10 days of oral therapy or one injection of intramuscular benzathine penicillin) is the treatment of choice because of effectiveness, cost, and spectrum of activity. Amoxicillin is equally effective and sometimes more palatable. Erythromycin and first-generation cephalosporins are options in patients with penicillin allergies. Treatment with antibiotics shortens symptoms by 16 hours.

There is no specific treatment for viral pharyngitis. Sometimes you can help relieve symptoms by having your patient gargle with warm salt water several times a day (use one half teaspoon of salt in a glass of warm water). Providing anti-inflammatory medicine, such as acetaminophen, can help control fever. Excessive use of anti-inflammatory lozenges or sprays may make a sore throat worse.

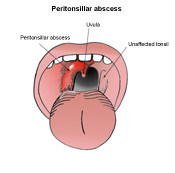

If you fear the condition is more problematic, such as massive swelling adjacent to one of the tonsils, a voice that resembles someone having a hot potato in their mouth, a deviated uvula to one side, or other conditions then you need to get that patient seen by a more advanced provider right away. Don’t let a peritonsillar abscesses or another truly emergency condition go without proper treatment.

So whichever the cause, if it’s one of the common infections, rest assured that you now have another tool to help you assess and treat this common ailment. Your patient/crew member will be back to singing “Deck the Halls…” in no time.